PNGi INVESTIGATES

Allegations of Serious Mismanagement at Kumul Agriculture

While there is no shortage of political intrigue over gas, oil and minerals in this country, agriculture remains the lifeblood of the nation. Despite the practical importance of agriculture, it has never received the level of public policy attention and state investment it warrants.

A brief glimmer of light emerged with the launch of a special state-owned company dedicated to agriculture, Kumul Agriculture Limited (KAL), which was incorporated on 13 November 2017 and given its public mandate via NEC Decision No. 221/2018.

Its purpose is “to identify, assess … [and] invest, in the development of sustainable agriculture projects across PNG”. By doing so, it is anticipated by government that KAL will contribute to local communities by providing “employment, local income and welfare development”.

2018, State Enterprise Minister William Duma with the newly appointed Board Members and advisors of Kumul Agriculture Limited (Source, https://www.kch.com.pg/new-agriculture-soe-gets-nec-approval-2/)

However, serious allegations of mismanagement have been made against the current and former KAL Managing Directors, by the Auditor General and KAL’s Board of Directors, respectively.

Analysis released by the Auditor General indicates that budgetary funds released to KAL, have been spent without a plan or budget. Only a small trickle of money has made it into agriculture projects. The majority of the allocated budget contributed by government (K10 million) has been spent on executive costs, travel and consultancies.

Included within this are significant sums paid to Commodity Management Partners Limited for consultancy work and car hire. Commodity Management Partners is a company 50% owned by KAL’s then Managing Director, Arthur Jones OBE.

While the Auditor General’s negative assessment focuses on KAL’s Managing Director, Arthur Jones, his departure from KAL in 2019, did not stop the criticism. KAL’s Directors have now raised the alarm over his successor Lyndon Sabumei.

In this report PNGi will detail criticisms made by the Auditor General and the KAL Board of the company’s successive Managing Directors. PNGi, however, does not have access to internal KAL records which would allow us to independently verify the criticisms made.

Attempts were made to contact Arthur Jones OBE and Lyndon Sabumei for comment. Jones’ response is detailed in the next section. He denies any managerial failures and claims the Auditor General findings are incorrect. He further notes that he left KAL in 2019, and has ‘no knowledge of what documentation or records the AG [Auditor General] was given access to’.

PNGi’s attempt to obtain a response from Mr Sabumei was unsuccessful (if he subsequently replies following the publication of this investigation, Sabumei’s response will be added).

Auditor General Probes Tenure of Arthur L. Jones OBE

The gazette notice appointing Arthur Jones as Managing Director of Kumul Agriculture is dated 11 September 2018, a position that was revoked two years later on 25 August 2020 (KAL financial statements from 2019 suggest Jones resigned on 3 June 2019).

Jones is an Australian businessman who has worked in the PNG mining, oil and gas, and agricultural industries for 35 years. He has been awarded an OBE, as well as the Independence Medal, for his work in these industries.

Despite these accolades Kumul Agriculture was flagged under his leadership in the Auditor General’s report (Part IV, 2019) with the rarely issued “adverse opinion”. In response to PNGi’s questions Jones states that the Auditor General findings are incorrect and he denies any mismanagement or conflicts of interest during his tenure at KAL.

The Auditor General’s contested report was based on KAL’s financial statements for the year ending 31 December 2018. The Auditor General concludes “that misstatements, individually or in the aggregate, are both material and pervasive”. Auditor General findings point to significant red flags.

First, the Auditor General makes several observations about financial management practices during Jones’ leadership of Kumul Agriculture.

The audit report claims KAL’s Managing Director “alone had the overwhelming financial authority to pre-commit [funds]. As a result, transactions worth K10,027,251 were approved by the CEO with insufficient source documents being retained to support those payments”.

It cannot be assumed this money was misused. However, from an auditing perspective this lack of documentation raises the risk of potential abuse.

Jones claims this statement by the Auditor General was incorrect, but he did not expand further in his answer to PNGi.

There was also allegedly an absence of proper procurement processes: “KAL had not implemented the standard ‘value for money’ procurement process. Accordingly, a significant number of payments were made under the CEO’s instructions and directives”.

Jones also claims this statement is incorrect.

In total, the Auditor General notes, “the State provided K10 million to finance the commencement of KAL’s operations during the year”. An additional K770,402 management fee was provided by Kumul Consolidated Holdings, and a further K159,083 was generated internally through crop sales.

The Auditor General states there was no annual budget or business plan for managing expenditure: “out of the total available funds [K10 million provided by the state, plus K0.93 million generated by income], K9,270,549 was spent during the year without a budget”.

Jones claims this is incorrect, but did not expand on this in his response to PNGi.

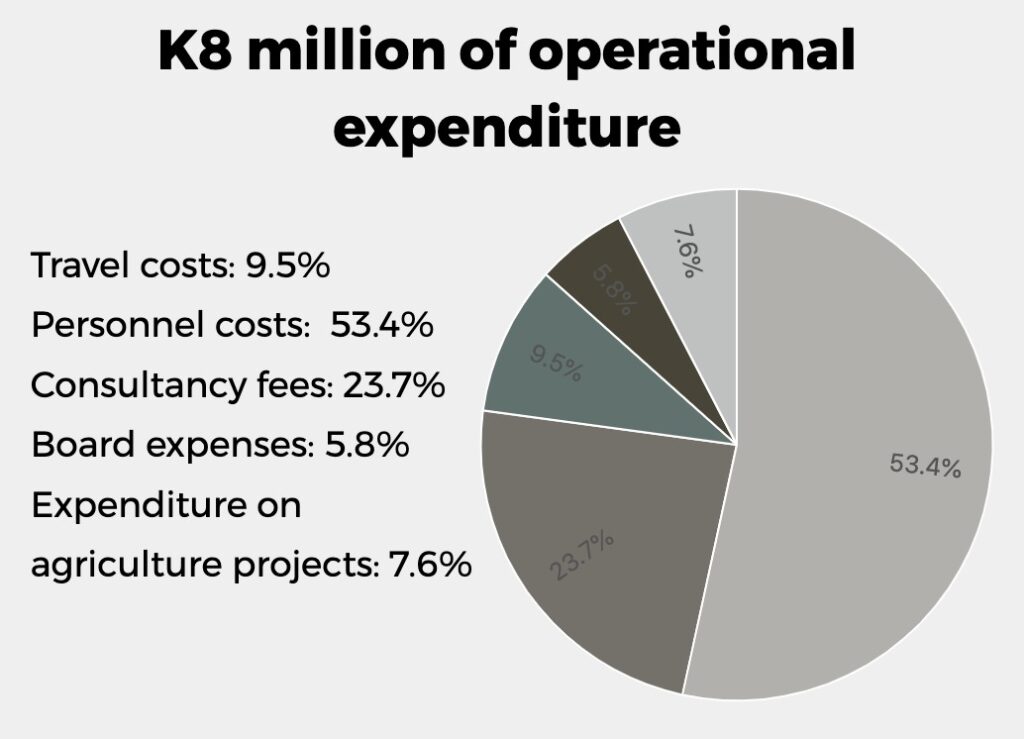

Arguably what is most concerning is that it appears from the audit only a trickle of funds made its way through to agriculture projects, the very reason for KAL’s existence. The majority of funds were apparently spent on executive costs, consultancy fees and board expenses, including some sizeable transactions involving Arthur Jones’ company, Commodity Management Partners Limited.

The Auditor General notes it was unable to “verify the validity and appropriateness” of the following payments:

- Personal expenses: K4,302,764 (62% of which are executive costs)

- Consultancy fees: K1,931,743

- Board expenses: K469,373

Jones claims the “documentation was thorough & complete” and further explains he has “no knowledge of what documentation or records the AG [Auditor General] was given access to”.

KAL’s financial statements break the cost of consultancy fees down into the following amounts K805,308 for financial consultancy, K244,182 for business management consultancy, K328,832 for plantation inspection and assessment, K244,136 for government liaisons and K309,285 for other consultancy.

KAL’s financial statements also indicate the highest paid executive received remuneration of between K580,001-K720,000. While it does not confirm if this was the payment received by Managing Director Arthur Jones, it is apparently the largest salary package paid by KAL and Managing Director is the most senior executive position within the organisation.

When asked if he was indeed the highest paid executive at KAL, Jones replied simply “I was designated and responsible to make it work”.

The financial statements also disclose the following payments to other executives within KAL who are not also Directors (thus it excludes Jones), which are stated to be George Brugh (General Manager), Ram Kumar (Operations Manager) and John Wilshere (Stakeholder Manager).

It also appears that Arthur Jones OBE benefited from payments made by KAL to Commodity Management Partners Limited (CMPL), a company which Jones is currently the 100% owner of (and in 2018/2019 Jones had a 50% shareholding).

The Auditor General notes with particular regard to CMPL.

“KAL paid a total of K161,013 to CMPL” for the rental, and then purchase of a vehicle, the Auditor General reports. The Auditor General also notes, “KAL purchased [the] motor vehicle at a cost of K75,000 from CMPL” after it had already been “hired from CMPL for … [Jones’] use… with a monthly rental payment that totalled K86,013”.

In another instance “a motor vehicle with a cost value of K100,000 was recorded in the asset register of KAL, [but] … was registered in the name of Commodity Management Partners Limited (CMPL)”.

When asked about these transactions Arthur Jones asserts in response “cash flow shortage required vehicles to be leased, [then] finally purchased. A cheap quality vehicle” [ed. Auditor General figures indicate K161,013 was spent leasing, then purchasing, a vehicle from Commodity Management Partners Limited].

The Auditor General pointed to other transactions involving CMPL. In particular, a transfer of funds into Jones’ personal bank account was noted: “an amount of K30,000 was paid to Commodity Management Partners Limited, a Company owned by… [Jones]. Subsequently, CMPL reimbursed K19,623 to KAL, and the balance of K10,377 was transferred to the personal bank account of the owner of the company (CMPL)”.

Looking at KAL’s financial statement it appears a further K255,000 was paid to CMPL for consultancy fees, which was not noted specifically in the Auditor General’s report.

When asked about how the conflict of interest between his role as KAL Managing Director and joint-owner of Commodity Management Partners Limited was handled, Jones replied: “No conflict of interest was entertained. A basic business principle”.

Beyond these individual payments to Commodity Management Partners Limited, concerns are also raised by the Auditor General over broader asset and financial management issues. For example, the Auditor General was unable to ascertain the accuracy or completeness of financial reporting about assets, investments and payments totalling K51,908,144, as listed below:

| Basis for “adverse opinion” | |

| Cash and Cash Equivalent | K1,677,826 |

| GST Receivables | K416,470 |

| Investment in Joint Arrangements | K24,100,000 |

| Investment in & Consolidation of Subsidiaries | K16,011,430 |

| Accounting for Biological Assets | No amount given |

| Group Tax (Salary and Wages Tax) | K445,991 |

| Operating Expenditures | K8,004,796 |

| Work in Progress | K1,251,631 |

In summary the Auditor General report details a state-funded company that apparently had poor managerial practices, controls and procedures. It was alleged to have been run by an executive who committed large sums of State funds without accountability, and didn’t meet his financial reporting requirements. These are the kinds of conditions that facilitated, the Auditor General argues, anomalous transactions, some of which featured the Managing Director’s own company.

While it cannot be assumed that these transactions were improper, it appears they warranted an expression of serious concern by the Auditor General given their features and the circumstances in which they were incurred.

Arthur Jones asserts the audit findings are incorrect. Jones maintains “documentation was thorough & complete, then”.

Jones also claims “much of our management/implementation was outsourced, meeting market rates. Had to be”.

Speaking more generally Jones states:

KAL’s life in my time was plagued by a chronic lack of reliable funding and no real coordination from most involved identities, in spite of NEC’s directions. To endeavour to find cohesion and purpose in the Govt environment was challenging, to say the least. My private enterprise background was focussed on progress over process. I resigned in 2019 as we were going precisely nowhere. Others became responsible for book keeping, audits, and ongoing operations. I have no knowledge of what documentation or records the AG [Auditor General] was given access to.

Board of Director minutes indicate Jones’ replacement by Lyndon Sabumei, has not put a stop to expressions of concern by oversight bodies.

Lyndon Sabumei's Tenure

Lyndon Sabumei was formally made Managing Director of Kumul Agriculture on 25 August 2020. However, Sabumei along with Malum Nalu were appointed to the board of various Kumul Agriculture subsidiaries in April 2020, including Kumul Coffee Limited, suggesting Sabumei’s involvement with KAL predates August 2020.

It appears Sabumei was suspended from his position as KAL’s Managing Director on 3 December 2020 in the course of KAL’s first board meeting.

Minutes of this meeting outline a number of allegations against Sabumei in a document filed with the Investment Promotion Authority on the 17 December 2020.

The Chairman of the board, Kapulu Mere, opens the meeting by discussing Sabumei’s absence, as well as that of the Company Secretary and CFO, Julian Dirihan.

Mere alleges that Sabumei and Dirihan were “deliberately doing everything to suppress the 1st board meeting from happening”. And that they “have been and continue to manipulate and sabotage the long delay of the board meeting for reasons of their own”. The Chairman does not state what these “ends” are. However, the board’s perception of these motivations become clearer throughout the meeting as the two main allegations are levied against Sabumei.

Peter Moorower, as well as “other directors”, reportedly share the sentiment “that there were many high-level matters (like vision & mission, corporate strategies, etc.) that must be properly discussed and executed by management and not play politics”.

In the rest of the meeting, the board members describe a persistent lack of clarity about what funds are available in the company, as well as how funds are spent.

For instance, one board member, Maio Ahi, “stressed the point that a letter must be written to the CFO asking him to provide the current status brief of the funds, especially after the recent K2 Million that was received”. Elsewhere a board member, Tiri Kuimbakul, opines that the CFO is likely being “coerced by the MD [Sabumei]”.

The board also suggests that these funds [K2 million] “may be being used despite a formal directive issued by the board that funds should not be used without a formal board resolution”. Board member Malum Nalu suggests that “two lots of K2 Million was paid to KAL within the space of a few months apart but the funds have been used elsewhere rather than community based projects. He also expressed that because of the inaction of management, the communities are losing trust in KAL”.

At the end of the meeting Lyndon Sabumei was apparently suspended with immediate effect. Julian Dirhiri was stripped of his secretary duties, but was permitted to carry on as Chief Financial Officer.

The Board also put a freeze on all new recruitments, consultancies, engagement of services providers, etc, until such time as a forensic audit of the books had been conducted.

Of course, Sabumei was not present at the meeting and thus was not able to respond to these allegations. Therefore, they should be treated as opinions of the Directors and not necessarily yet established facts.

Attempts by PNGi to obtain comment from Sabumei were unsuccessful.

Conclusion

Agriculture is an important industry in Papua New Guinea, employing 85% of the country.

The stated aim of Kumul Agriculture is to develop the agricultural sector, and through doing so, to provide better social conditions for local communities.

The allegations against KAL executives suggest that owing to an absences of transparency and rigorous managerial oversight, these aims have been frustrated. Of course, it should not be discounted that some of these alleged failures may be a result of the lack of political planning for KAL’s operations.

Nonetheless, the conditions have been laid for what appears to be a lot of fruitless spending that primarily added to KAL’s bloated executive costs, if we accept the findings of the Auditor General.

This case also points to another significant challenge, those tasked with the management of publicly owned companies are at times poorly prepared for the roll, in particular meeting their responsibilities under the Public Finance (Management) Act and associated financial instructions. Tied to this is the need to recruit managers with a strong sense of public service, with all that this entails.

This case also points to the lack of operational accountability within state owned enterprises. Systemic problems ought to be remedied well before they need to be aired by the Auditor General. And when they are aired, beyond the odd response from management, there is a lack of mechanisms to ensure Auditor General recommendations are enforced.

Hence we see the same problems censured in Auditor General report after report, without any apparent change within the institutions subject to criticism for significant failings.

Of course, the buck does not stop necessarily at civil servants, who operate within the boundaries set for them by the political leaders of the nation. When political leaders are failing the basic test of good government in the public interest, the environment is set for the fish to rot from the head down.