THE TOKAUT BLOG

Investigating the Electoral Commissioner: A Citizens Guide

In today’s Tokaut Blog criminologist Dr Kristian Lasslett, demonstrates a series of simple techniques – employing PNGi tools and freely available online resources – which citizens can use to investigate the Electoral Commissioner, Patilias Gamato. The results of this citizens’ inquiry reveal a man who on successive occasions has breached his legal duties as a public and corporate official …

Serious questions have been raised over the integrity of the 2017 elections. In the hot seat is Electoral Commissioner, Patilias Gamato. Politicians, past and present, have rated the election amongst the worst in Papua New Guinea’s history.

In a further blow to Gamato, the Election Advisory Committee has quit after its members claimed they were denied access to the electoral roll and polling booth information.

Sir Mekere Morauta suggested ‘Patilias Gamato should immediately resign. He has failed Papua New Guinea’. Others have called for a Commission of Inquiry.

While nothing can replicate the rigour of an official body empowered in law to question witnesses and access confidential documents, everyday citizens can begin to fight back by informing themselves using a series of basic investigative techniques and tools.

Map linked entities

First, to effectively scrutinise the record and integrity of senior public & corporate officials, we need to map the organisations they have been responsible for in their careers.

A basic google search can render insights into past public responsibilities – scan the findings for news reports, pdfs (official documents/reports), and institutional websites. Results can be further refined using time bound limits e.g. 01/01/2006 – 01/01/2012.

If the website is down, google allows you to access cached versions, or you can use archival tools like ‘The Waybackmachine’.

In Gamato’s case we can document a number of public roles based off media reporting, court case reports and online institutional documents:

- In 2001 he served as Lae District Administrator.

- By 2005 Gamato had been appointed Deputy Administrator for Morobe Province, working alongside the province’s Administrator, Manasupe Zurenuoc, who would go on to become Chief Secretary under Prime Minister O’Neill in 2011.

- At various times between 2007-14 he served as Acting Administrator and Deputy Administrator in the Morobe Provincial Government.

- In July 2015 he was confirmed as Administrator for Morobe Provincial Government.

- Finally, in November 2015 Gamato was appointed Electoral Commissioner.

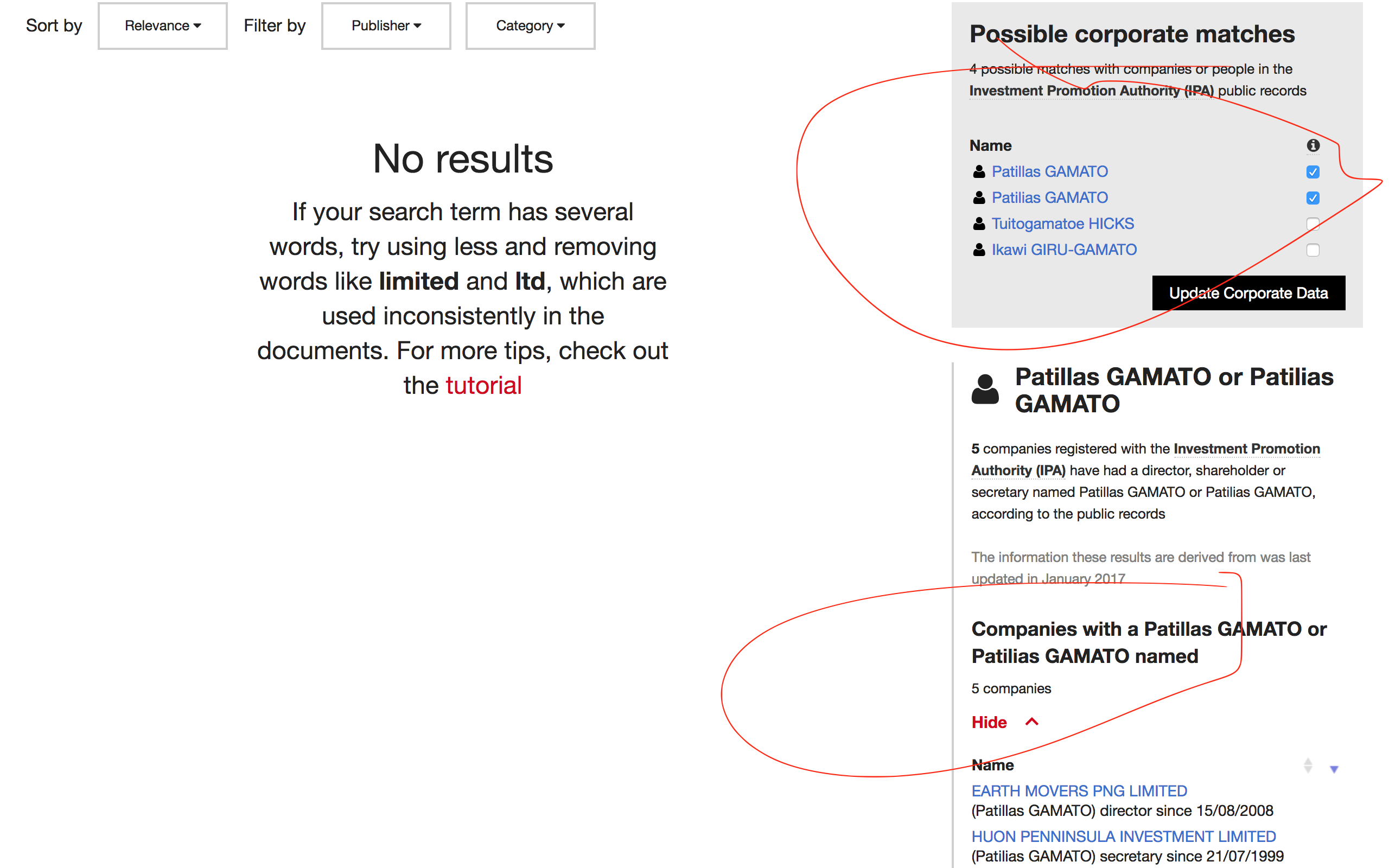

To uncover the corporate roles assumed by Gamato, we can turn to PNGi Portal for help.

The trick when using this new database is to keep the net wide. Search using Gamato only, excluding Patilias. The search engine will detect records connected to Gamato, and will offer known variations in the spelling of his first name e.g. Patilias, and Patillas.

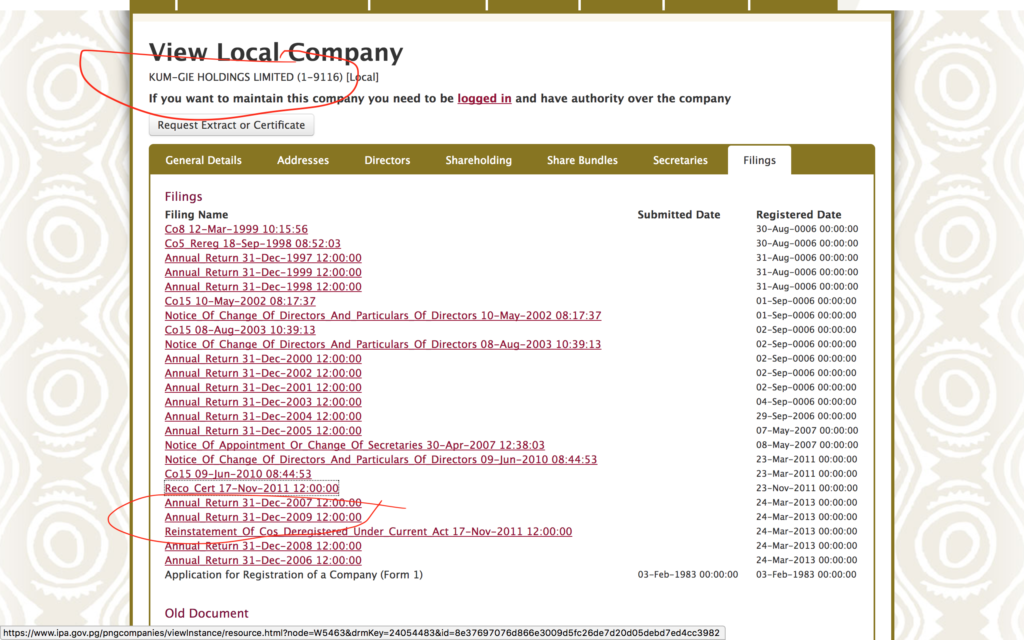

PNGi Portal indicates five corporations are connected to Gamato. Three of the most important are Kum-Gie Holdings, Earth Movers PNG Limited, and Sarawaget Risos Limited, which form part of the Morobe Provincial Government’s business arm.

We now have a list of key entities managed by Gamato:

- Morobe Provincial Government

- Provincial government business arms, Kum-Gie Holdings, Earth Movers PNG Limited, and Sarawaget Risos Limited.

- Electoral Commission

- Other corporate entities, Huon Penninsula Investments Limited, and Yekora Resources Development Company Limited.

Accordingly, we can take steps to scrutinise their performance during Gamato’s tenure using certain research techniques.

Performance as a provincial administrator

There are a number of sources that can be used to evaluate Gamato’s performance as an administrator – including, for example, Auditor General, Public Accounts Committee, Commission of Inquiry, and Ombudsman Commission reports, complimented by the National and Supreme Court case archives.

Relevant evaluative criteria includes:

- The Public Finances (Management) Act 1995.

- The Leadership Code.

- Good governance and administrative norms.

When scrutinising good governance and public finance management, an important source of information is Part III of the Auditor General’s report on public accounts, which focuses on provincial governments. They can be browsed and downloaded via PNGi Portal.

The most recent, available scorecard for Morobe Provincial Government, which covers a period when Gamato served both as Deputy and Acting Administrator records significant failings and weaknesses. The Auditor General notes:

- Poor maintenance of property and licensing registries, prevented the Auditor General from assessing whether revenues had been properly collected by the provincial government. The Auditor General observes: ‘[An] absence of [real property] registers and lease agreements’; ‘motor traffic registry files had not been properly maintained’; and ‘there had been no proper management, control and monitoring of liquor licensing and the collection of revenues due to the Provincial Government’.

- With respect to public procurement, ‘three quotations had not been obtained in most instances prior to the purchase of goods and services … Funds totalling K9,795,168 paid to District Treasuries for maintenance of schools, roads, bridges, airstrips and wharves had not been monitored by the Provincial Works Unit to ensure that the funds paid were spent on the intended projects … Individual project files in relation to total expenditure of K4,902,761 for the construction and maintenance of roads, foot bridges, buildings, installation of gas and water, and fencing of schools were not available, although requested’

- ‘Excessive funds which could have been used to purchase vehicles were instead spent on hiring vehicles’.

- ‘It was not possible for me to ascertain the correct total expenditure figure to compare against the total appropriation of K361,319,500. The information on the public servants and the teacher’s salary had not been provided. The total salary figure was misstated in the financial statements’.

- Records relating to the government’s real and automotive property were missing, consequently it was impossible for the Auditor General to evaluate whether these assets had been properly managed.

- ‘No evidence was provided to show that the payroll reports for both national and provincial governments had been checked by human resource officers to ensure that there were no ghost employees and all salaries and allowances were paid according to the approved rates’.

- ‘The Internal Audit Office (IAO) lacked appropriate human and necessary logistical resources to function effectively’.

The report contains many other critical remarks, including a note that the Provincial Government failed to respond to the Auditor General’s findings.

Of course, not all these flaws may be attributed to Gamato. Nevertheless, as a senior Morobe administrator, he must presumably assume some of the responsibility for these negative findings.

And while it is certainly true other provincial administrations are in a similar state of financial and administrative disrepair, two wrongs dont make a right.

Lets turn now to Gamato’s record as a corporate executive.

Performance as a company Director

Gamato has acted as company Director for four entities, and Secretary at a fifth.

The duties and responsibilities of corporate personnel are set out in the Companies Act 1997.

For example section 215 states that Directors must submit accurate annual returns, within 14 days of the company’s annual meeting. Failure to do so is an offence and renders every Director liable to a fine of up to K10,000.

Using this basic criteria – although of course there are other Director responsibilities – we can begin to determine whether as a Director, Pamato conducted himself in accordance with the law.

Owing to improving levels of corporate transparency in Papua New Guinea, we can make this determination by consulting the company registry managed by the Investment Promotion Authority.

Consultation of the corporate register indicates Pamato – if registry records are accurate – has potentially fallen foul of the Companies Act 1997, Section 215, on 32 occasions.

Were the maximum fine levied for each apparent violation, this would amount to K320,000.

The Auditor General also warned, when scrutinising the Morobe Provincial Government’s investments:

It is common knowledge that the Provincial Government has a business arm, namely Kumgie Holdings Limited and its subsidiaries. The Provincial Government did not report any investments in statement ‘F’ of the financial statements. Also, no Investment Register was provided for audit.

The Auditor General does not refer to Earth Movers PNG Limited or Sarawaget Risos Limited. It is not clear whether these financial interests were declared by the Morobe Provincial Government.

Performance as Electoral Commissioner

Gamato was appointed Electoral Commissioner during November 2015. He has already generated a documentary footprint, which casts some light on his performance.

This footprint can be found in the National and Supreme Court archives, curated online via the PACLII website.

Two cases of particular relevance appear when searching the term, Gamato.

- Parua v Gamato [2017] PGNC 48; N6671 (6 February 2017)

- Wakias v Gamato [2017] PGNC 62; N6687 (17 March 2017)

In Parua v Gamato we discover that Margaret Parua provided legal services to Gamato, in his official capacity as Electoral Commissioner. The court states that she was instructed to work on ‘electoral matters within the Southern Region of Papua New Guinea’.

It was alleged by Ms Parua that the Electoral Commission failed to pay K7,324,420.83 in bills for work conducted between 2014-2016.

The Court agreed, noting ‘the plaintiff received instructions, performed the services, submitted invoices some of which were paid and there remains outstanding the sum of K7,324,420.83’.

Perhaps of greater relevance, given the current controversy, is the case Wakias v Gamato. It is alleged by David Wakias he was unlawfully removed from his position as ‘Election Manager of Southern Highlands Province’.

The court observes:

He held the position until his appointment was revoked by the Electoral Commissioner on 4th October 2016 and redeployed to Port Moresby as a support staff in the Operations Division. In his place a Mr. Jacob Kurap was appointed Acting Election Manager.

The statement of facts continue:

The First Defendant gave no reasons for revoking the Plaintiff’s appointment nor did he charge the Plaintiff for any disciplinary offence or breaching his contract of employment. The Plaintiff was more or less left in the dark, so to speak and immediately the next day, 5th October wrote a letter of appeal to the First Defendant and pointed, amongst other things, that he was the substantive holder of the position thus, could not be removed at will or on short notice, that he had overseen two previous elections in Southern Highlands Province without much trouble and that Mr.Kurap had not applied for the position. He received no response to this letter although the First Defendant said that by the time the letter was brought to his notice, the Plaintiff had commenced these proceedings. The lack of response together with the lack of reasons left him to wonder why he was asked by the Electoral Commissioner on short notice to leave Southern Highlands Province and caused him to file these judicial review proceedings. Meanwhile, Mr.Kurap was one of the unsuccessful applicants for the subject position in 2014 while working for Telikom (PNG) Limited. He then moved to Southern Highlands Provincial Administration as its legal officer when he was handed the job after the Plaintiff’s appointment was revoked.

The Courts found in favour of Mr Wakias, noting:

- He had a ‘long distinguished career and service as an electoral officer’, including the ‘supervision of two previous elections without much trouble’.

- His dismissal ‘not only constituted a breach of contract but a denial of the Plaintiff’s right to natural justice under Section 59 of the Constitution’.

- Mr Wakias’ replacement, Jacob Kurat ‘was appointed without applying for the position and this is regardless of an earlier application which was unsuccessful. Furthermore, it may be that his appointment was only to act on the position pending appointment of a permanent officer but as it has been revealed, the circumstances did not justify it. Another matter was that, there is no evidence of consultation with the Secretary of the Department of Personnel Management before the appointment was made’.

- ‘It was illogical and defies common sense when a decision-maker in the position of the First Defendant [Gamato] would over-look the Plaintiff’s outstanding career and service to the province, that his appointment as Returning Officer has not been revoked, his family welfare and inconvenience and revoke/ relocate him to Port Moresby on a temporary basis … These matters have led me to conclude that the decision was unreasonable as no person in the position of the First Defendant would have arrived at such a decision’.

- ‘In relation to the newly appointed Acting Election Manager, he lacked qualification and experience. He was hand-picked from the provincial administration by the First Defendant at the request of the Acting Provincial Administrator for no good reason’.

- ‘I accept the submissions of the Plaintiff. The matters pointed out by the Plaintiff point to a case where there had been serious breaches of the substantive and procedural laws which are so flagrant and wilful, thus justifying a grant of orders sought by the Plaintiff’.

As a result the Court ordered:

- The decision of the First Defendant to revoke the appointment of the Plaintiff as Election Manager of Southern Highlands Province of 4th October 2016 and replace him with Mr. Jacob Kurap is null and void, and of no effect.

- The decision of the First Defendant to revoke the appointment of the Plaintiff as Election Manager of Southern Highlands Province of 4th October 2016 and replace him with Mr. Jacob Kurap is brought into the Court and quashed.

- The Defendants shall reinstate the Plaintiff to the position of Election Manager of Southern Highlands Province forthwith.

Conclusion

Through a number of investigative techniques, employing tools such as PNGi Portal, PACLII, and the IPA, it is possible for anyone to conduct a citizen’s investigation into public or corporate officials.

By applying these techniques to the Gamato case we have already uncovered significant issues, including:

- Evidence of mismanagement within a provincial government, where Gamato was a senior administrator.

- Records indicating Gamato breached the Company Act 1997 on at least 32 occasions when serving as a Director.

- Illegal dismissal of an employee, in his capacity as Electoral Commissioner.

These are warning signs, yes, but it cannot be deduced from this evidence that Gamato has necessarily failed to discharge his duty as Electoral Commissioner.

That allegation requires a fair and transparent probe, by an independent authority, through a public hearing, with wide terms of reference, where the records are available for public scrutiny, and Gamato has a fair chance to defend his performance.

The Gamato case aside, mismanagement, abuse of power and corruption across the globe is finding one if its greatest enemies are citizens, professionals, researchers, activists and journalists, weaponised with new and novel ways of investigating the nefarious dealings of the elite, and uncovering the political and commercial systems that allow such activity to thrive.

Everyone can play a role in this effort, through sharing data, improving investigative techniques, and sharing reporting when it comes to hand, with friends, family and colleagues.

Injustice thrives when the people of a nation feel powerless and demoralised. Investigation, public reporting and public debate is one, of many laudable ways, we can all express our agency, resist abuse, and do something to change the political systems that deny ordinary people a chance to realise their dreams and capabilities.

Of course, uncovering the facts is one thing, its what we do with them, that can change the course of history.