PNGi INVESTIGATES

The Birth of Kleptocracy: A Eulogy for the Nation

In the late 1980s Judge Tos Barnett prepared what would become a classic study on forestry sector corruption – The Commission of Inquiry into Aspects of the Forestry Industry.

During his investigation, Judge Barnett cast a spotlight on the Angus Group of Companies and their bid to secure the Gadaisu forestry permit area in Central Province.

The story of the Angus Group is the story of a kleptocracy taking its first steps – a nation ruled by thieves.

Although this sordid tale of corrupt conduct at the very top took place three decades ago, the scheme exposed by Judge Barnett is a blue print of what is now commonplace in Waigani.

It centres on one of the nation’s founding fathers, Edward “Ted” Diro. Diro, the inquiry found, worked hand in glove with one of the country’s most respected lawyers, to set up an illicit scheme that signed over a lucrative forestry permit to Malaysian loggers. The plan was to rip the life out of the area, with utter disregard for the environment and local landowners. Then the most valuable logs would be exported employing a fraudulent scheme to conceal profits from the taxman, using a crooked bank in Hong Kong and British tax haven Jersey. The spoils would be split between the PNG and Malaysian conspirators.

The then Forestry Minister, Ted Diro, used trust agreements to hide his beneficial interest in this illicit scheme. A code-word was even employed, “Anthony”, to ensure Ted Diro’s name was not explicitly mentioned in documents.

When the scheme went belly up, the PNG conspirators attempted to defraud their Malaysian partners.

A trail of environmental devastation was left, dozens of local employees lost their jobs, and landowners were left with environmental desolation and empty pockets.

The big names caught up in this scandal were summarised by Judge Barnett:

At the commencement of the inquiry I summonsed all the business records of Angus (PNG) Pty Ltd and Commission staff analysed them most carefully. The documents studied supported the rumours and indicated very serious misconduct by Mr E R Diro, the former Minister for Forests who at the commencement of the Inquiry was Minister for Foreign Affairs and leader of the Peoples Action Party. They also showed that the former Governor General, Sir Tore Lokolo, was involved as Chairman of Angus, that Mr Gerard Kassman, former President of the PNG Law Society had played a significant role, that Mr Oscar Mamalai, then Secretary of the Department of Forests, had questions to answer and that some notable foreigners would be implicated in the Inquiry.

Corrupt politicians, fixers drawn from the upper echelons of the legal community, complicit civil servants, the manipulative arm of foreign businessmen, and trashed resources, it is a story that has been written a thousand times since, with new names and new actors, but the same plot line. Rarely though, if ever, is the story told with the vivid detail gathered by Judge Barnett.

So in honour of this treasure trove of materials that trace the birth of today’s kleptocratic regime, PNGi retells Barnett’s surgical inquiry into the Gadaisu forestry permit. Only by understanding how we arrived at our current destination, can we change the nation’s future direction.

Diro's Malaysian Secret

This story begins in 1984.

Newly elected Member for Central, Mr Ted Diro, was fast becoming a major Papuan political powerbroker following a successful military career. Diro, the Commission of Inquiry observes, was also working closely with Malaysian businessmen from the Angus Group to illegally seize valuable logging rights.

Angus Group was based out of Singapore.

Image: Lieutenant Colonel Ted Diro escorts Queen Elizabeth in her 1974 visit to PNG

The Commission of Inquiry (CoI) notes that Diro teamed up with former President of the PNG Law Society, Gerard Kassman, Foong Chin Cheah, who was acting on behalf of the Malaysian Angus Group, and John Kasaipwalova. Both Kasaipwalova and Kassman would become involved in Diro’s Peoples Action Party.

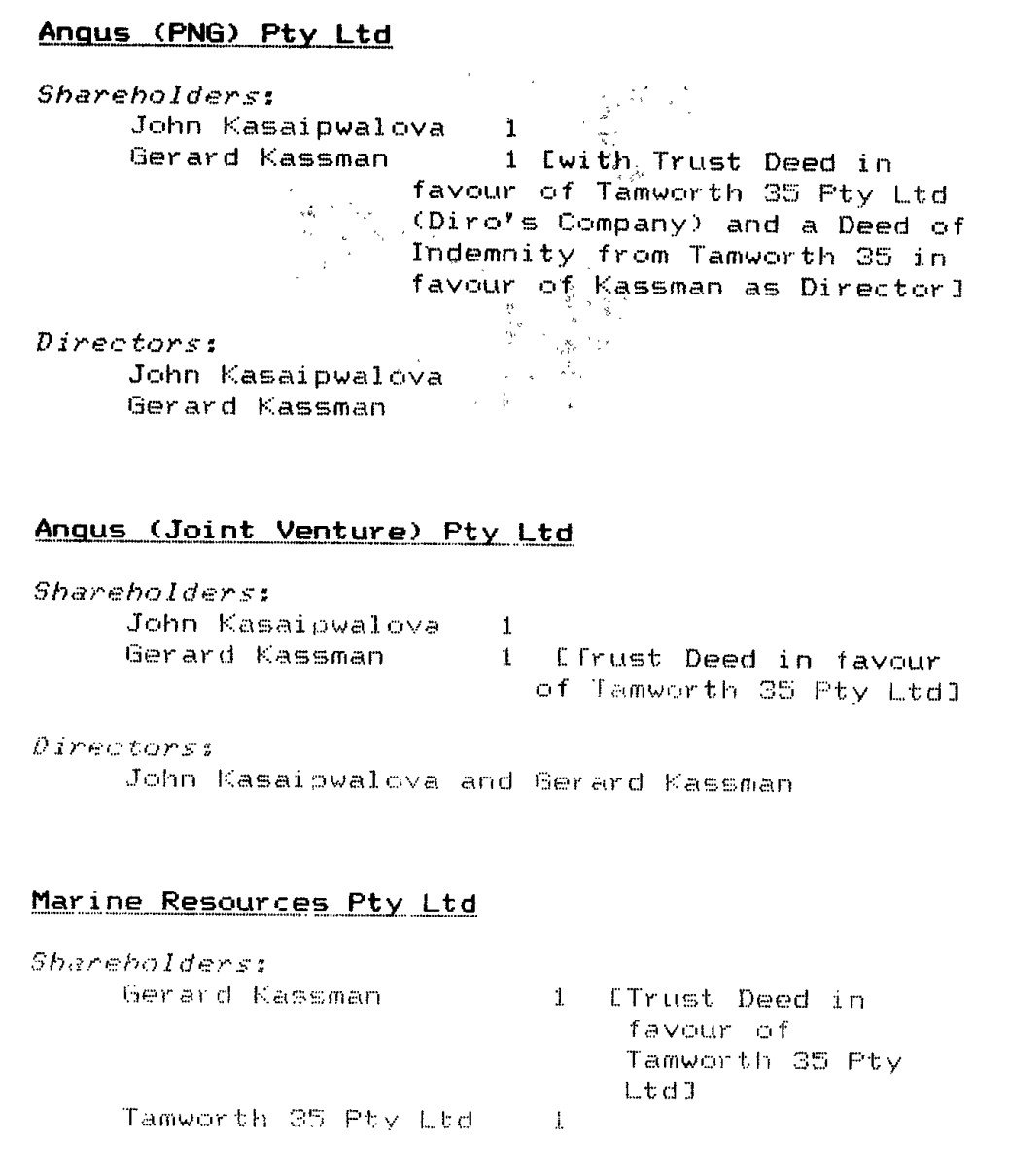

Three local shelf companies were used to set-up Angus Group’s PNG operations – Angus (PNG) Pty Ltd, Angus (Joint Venture) Pty Ltd, and Marine Resources Pty Limited.

Initially the Member for Central Province, Ted Diro, held significant beneficial interests in all three through the company Tamworth 35 Pty Ltd.

This, however, was not apparent from the public share registry. Gerard Kassman was publicly listed as the shareholder. What the public didn’t know was that Kassman held the shares on trust for Tamworth 35 Pty Ltd, a company owned by Ted Diro.

Trusts are a legal mechanism that allows a settlor to vest legal title over property to a trustee, who then manages the property on behalf of a beneficiary. Politicians and public officials the world over use Trusts to conceal their interests in a company, while still ensuring they are the beneficiary of any profits made. Because there is no register of Trusts, the public has no way of knowing a Trust exists.

In this instance, there were other benefits for Diro and his Malaysian business partners.

Because the companies were owned by PNG nationals rather than their Malaysian backers, they were able ‘to avoid the necessity of obtaining approval under the NIDA Act [National Investment and Development Authority Act] and to gain the more favourable treatment afforded to National Companies in matters of resource allocation and development’.

Judge Barnett notes ‘subsequent manipulation of share issues however show that there was always an intention to have a secret majority foreign ownership situation’.

According to Barnett the two key foreign principals in Angus were Mr M A Ang and Mr Tan Sri Ghazali Shafei. Their interests were handled in PNG by Malaysian National, Foong Chin Cheah who has been linked to various other scandals since.

In addition to being a partner of this Malaysian consortium, Diro was receiving other benefits as a result of this covert relationship.

Judge Barnett observes ‘for instance Mr Diro’s company Tamworth No 35 rented its apartment No.306 Pacific View to Angus for K400 a month and Angus Investments was beginning to make various payments on his behalf’.

Image: Diro rented his Unit at the iconic Pacific View Apartments to the Angus Group

On 1 November 1985 it was agreed at Gerard Kassman’s office to restructure the Angus Group in PNG. Angus (PNG) and Angus (Joint Venture) would each issue a share to Malaysian national, Foong Chin Cheah. To ensure the firms qualified as national companies – which required 75% national ownership – an extra share was issued to Diro’s company Tamworth 35.

In the case of Marine Resources, F C Cheah and Victor Lee were brought in. Mr Cheah was also made Managing Director of all three companies, while Ted Diro was appointed Chairman of the Board.

The documentation for these changes was prepared by Kassman and Kasaipwalova. Before they could be submitted, there was a change of government. On 27 November 1985 Diro was made Forestry Minister in the Wingti Government, to the documented delight of Cheah and Kasaipwalova. Their man was now in charge!

Jackpot! Diro becomes Minister for Forests

Judge Barnett observes

As Minister for Forests he [Diro] was now bound, under Section 6 of the Organic Law on the duties and Responsibilities of Leaders, to sever his links with Angus and to disclose the whole situation to the National Executive Council and to the Ombudsman Commission … Despite Mr Diro’s cover-up and blocking tactics throughout this long inquiry the evidence clearly shows, and at the end he finally admitted, that he chose to retain and in fact to increase, his beneficial ownership in Angus, to hide that fact by a series of trust arrangements, and to make no disclosures to anyone.

It is also noted, ‘to clean up the public record Mr Diro resigned as Chairman of the Angus (PNG) subsidiaries but he continued to receive substantial benefits. He also began actively to use his position as Minister to promote the interests of Angus (PNG) Pty Ltd’.

The CoI continues: ‘The Angus Group immediately appreciated the importance to it of Diro’s appointment and realised that it put the group in a very favourable position, but that Diro would now have to “maintain a very low profile” [F C Cheah] in company affairs’.

To that end, Sir Tore Lokoloko took over as Chairman of Angus PNG. Sir Tore had been Governor General from 1977 until 1983.

With Diro now in charge of the forestry portfolio, a proposal for the Gadaisu forestry permit area was submitted by Angus Group.

The Commission of Inquiry notes: ‘while the [Forestry] Department was urgently trying to find out some details about Angus (PNG) Pty Ltd, and assessing the proposals, Mr Diro and his wife Veitu Diro accepted an invitation by Angus Singapore and flew to Singapore and Malaysia with the new Angus PNG Chairman, Tore Lokoloko at Angus’ expense’.

Senior Forestry Departmental officers reviewed the application and unanimously rejected it. They argued Angus had no experience or expertise, failed to disclose essential financial details, was vague about the proposed structure and contracting arrangements, and was not registered with the Department of Forests.

Nevertheless, several days after his trip to Singapore – paid for by Angus – Minister Diro directed the Forestry Secretary to ‘take immediate steps to issue the Timber Permit in due course’ to Angus, a company in which he held a hidden interest.

The Secretary executed the Minister’s directions despite opposition from senior departmental officers, ordering on 11 February 1986 that a timber permit be issued to Angus PNG.

The Secretary personally negotiated the terms of the permit. He even went to the unusual step of allowing Angus to type up the agreement ‘outside the Department under Angus’ supervision’.

‘During the negotiations’, the CoI observes, ‘while Minister Diro was being briefed and consulted by the Secretary, the Minister was also in regular, secret contact with Mr Kasaipwalova’.

By this stage the shareholding arrangements had shifted slightly in form, but the substance remained the same – Diro maintained a 35% stake via a proxy, while the Malaysian investors had a majority stake, most of which was held through a frontman in a bid to circumvent NIDA Act requirements.

Judge Barnett summarises the situation:

Judge Barnett summarises the situation:

The reasons for Mr Diro’s determination to grant the permit to Angus are easy to see. He was a 35% beneficial owner of the company … he held very high hopes of making a great deal of profit for himself personally and possibly, as he later claimed, for his political party. If it is true, as he now claims, the he also had high hopes of benefiting the Magi Wopten people, I can see no evidence of it. In fact the evidence suggests he was party to the reckless destruction of their forests, by virtue of the logging practices adopted, and party to a plan to systematically cheat them of their rightful profits, by the marketing schemes adopted [grounded in transfer pricing, see below].

Transfer Pricing, Tax Evasion and Environmental Catastrophe

When logging operations began Angus PNG was in a difficult financial position, having ‘desperate liquidity problems’. This prompted a rip and run approach.

The CoI observes:

Early reports by Forestry Inspectors show that the logging techniques caused great wastage and environmental damage. This was made worse by the fact that they were threatened by fear of imminent financial collapse both in Singapore and Papua New Guinea. To keep its creditors happy Angus needed large profits from log shipments quickly.

The report continues, ‘to achieve this its operators chased after pockets of the highly priced rosewood whenever they were reasonably accessible and left the less valuable species … To gain quick access to a site for the log pond the company bulldozed Sabiribo Village from its peaceful situation on the beach and left the people to rebuild a temporary “shanty” village perched on a bare hillside’.

Coupled with environmental destruction, Angus aimed to inflate its profits through transfer pricing, a practice of understating profits earned in PNG, to avoid paying tax.

Image: Transfer pricing explained (Source: https://taxandsupernewsroom.com.au/transfer-pricing/)

The Commission of Inquiry observes:

It is quite clear from the documentary evidence that from the very early days of the Gadaisu timber operation there was a conspiracy between M A Ang, Tan Sri Ghazali Shafei, F C Chea, J Kasaipwalova, and once he joined the group a bit later, Charlie Koh. The conspiracy commenced with the very first contract and it involved transferring USD10 of the true price per cubic meter, across the total contract shipment, to Angus Singapore.

It is noted by the Commission: ‘The potential for transferring such profits was greater for Rosewood because there was a great difference between MEP [minimum export price, set by Dept. of Forests] for Rosewood and actual market price. Rosewood thus formed the basis for illegally transferred profits for the first shipment’ (in other words, Rosewood could be bought from Angus PNG by Angus Singapore at an artificially low price, so the former did not make a profit, thus evading corporate tax in PNG).

Despite these illicit methods, the operation struggled. With tensions high between Angus Singapore and Angus PNG, Mr M A Ang for Angus Singapore arrived in PNG. He met with Ted Diro, Sir Tore Lokoloko and John Kasaipwalova.

It was agreed the former Law Society head, Gerard Kassman, would replace Kasaipwalova as Company Secretary. Touche Ross would be appointed Company Auditor.

They also changed the beneficial ownership arrangements. The 31% stake held by Kasaipwalova on trust for Angus Singapore, would now be held by Sir Tore.

M A Ang was subsequently arrested, and sentenced to eight years prison in Malaysia, for criminal breaches of trust associated with another company, MOIC (KL).

In the second round of export contracts, the the Commission of Inquiry notes, Angus embarked on a more ambitious transfer pricing scheme.

This scheme, Judge Barnett notes, created the potential for ‘raising a non-disclosed offshore, tax free profit of USD9.408 million’.

The scheme would take place through a Jersey company, Valouse Ltd ‘into whose Hong Kong account at BCC [Bank of Credit and Commerce International] the offshore profits were to be paid’.

Jersey and Hong Kong are jurisdictions where corporate and banking affairs can be conducted under a cloak of secrecy. Jersey has the added benefit of being a haven where there is a 0% corporate tax rate.

The proposed banker, the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, specialised in facilitating financial crimes. It was eventually shut down after a series of scandals.

According to a US Senate Committee inquiry the Bank was ‘set up deliberately to avoid centralized regulatory review, and operated extensively in bank secrecy jurisdictions. Its affairs were extraordinarily complex. Its officers were sophisticated international bankers whose apparent objective was to keep their affairs secret, to commit fraud on a massive scale, and to avoid detection’.

Angus proposed that management of the Jersey based Valouse Ltd would be done by ‘two nominee directors from Arthur Young acting on a standing instruction from the beneficiary shareholders’. Edward Diro would receive 35% of the profits. The document noting his share of the loot, used the code word “Anthony” to conceal Diro’s identity.

The commission notes:’Mr Diro’s own financial situation at that period was quite desperate. Evidence from his bank files and income tax returns shows he was facing bankruptcy for having recklessly “milked” his private companies for political purposes.

Judge Barnett concludes:

As a matter of fact, therefore, I find that Mr E R Diro, as well as Tan Sri Ghazali Shafei, C Koh, F C Chea and J Kasaipwalova all had full knowledge of, and participated in the planning of this [transfer pricing] scheme … it appears to have been a detailed conspiracy to cheat and defraud the State of income tax and customs duties and to cheat [the landowner company] Magi Wopten Development Pty Ltd. of its share of the true profits.

What Goes Up Must Come Down

Before the second, more grandiose transfer pricing scheme could be executed, things went sour.

On 3 November 1986 ‘the Angus Group in Singapore went into liquidation and the liquidator began to inquire about the debts owed to it by Angus (PNG) Pty Ltd’. ‘The PNG company was also in very bad shape and clearly unable to pay its creditors’, the CoI observes.

As a result the Forest Industry Council took over the running of Angus PNG and dropped the second transfer pricing scheme.

As Angus went into financial flat line, ‘Mr Diro finally approved the issue of a show cause notice allowing one month to show cause why the permit [held by Angus] should not be cancelled’. It was served on 5 November 1986.

Then the ship broke apart.

In a last ditch bid to realise the major profits on offer from the transfer pricing scheme, Angus PNG attempted to split from its Singapore parent company through a fraudulent share issue scheme.

The CoI observes ‘the PNG Directors first turned upon Singapore’s man F C Cheah and demanded his resignation’. At a ‘General Meeting on the 19 November, from which Cheah was absent, then approved an increase in authorised capital from K10,000 to K400,000. 89,900 shares were allotted to the Chairman Sire Tore Lokoloko, and 127,600 one kina shares were allotted to John Kasaipwalova’.

Judge Barnett observes ‘the legal advice for the share issue was provided by Angus’ lawyer G Kassman but his involvement did not stop there. As a Director of the company, and as Company Secretary, Kassman must also accept personal responsibility for what happened’.

Barnett adds ‘he must have known Angus Investments Pte Ltd was then in liquidation and that fact may well have given him confidence that the fraud about to be attempted would either go unnoticed’.

As a result of this ‘fraud’ documented by the CoI, Angus Singapore’s interest in its PNG subsidiary went down to 2.26 per cent.

However, by this stage Diro thought that Angus PNG ‘was a goner’, and worked behind the scenes to cancel its permit.

The Commission adds

He was in fact working with the very compliant Oscar Mamalai [Forests Secretary] to cancel Angus’ permit and to issue a new permit, in record time, to a company previously unknown in Papua New Guinea, Goodwood Pty Ltd which wished to operate both the Gadaisu (including Bonua-Magarida) and Kupiano permit areas. The speed with which this was being arranged was absolutely astounding and highly suspicious.

Angus PNG was put into liquidation.

In the end it had assets of K193,000 and debts of K1.6 million.

The CoI notes ‘sixty national employees were found abandoned at Sabiribo village without wages or food … No royalties had been paid under Angus’ management and there was some K27,000 outstanding. Likewise the premium due to [Landowner firm] Magi Wopten of K6 per m3 had not been paid’.

‘On the other hand’, Judge Barnett observes, ‘the very high salaries of F C Cheah and J. Kasaipwalova (K50,000 p.a.) plus very generous accounts and benefits were [still] being paid’.

The liquidator cancelled them immediately and terminated both men’s employment.

Finally ‘the resource itself was badly damaged, with blocked and polluted streams, and a substantial amount of wasted timber left both standing and felled’.

A Eulogy for the Nation

Ted Diro and the Gadaisu forestry permit, is the story of PNG’s infant kleptocracy taking its first steps.

And like with any first step there was a stumble. Where Diro failed, his successors would succeed.

What Judge Barnett documented was the blueprint for this success.

It begins with utter disregard for the people of PNG, the environment, the Constitution, Leadership Code and Criminal Code. The only loyalty in kleptocracy is to money.

Then comes the sham fronts. Trust Agreements, and foreign bank accounts, are the stock trade used to hide beneficial ownership and launder illicit proceeds.

Helping set up these sham fronts, are lawyers, accountants and bankers. And these are not lawyers, accountants, and bankers, sitting in some two-bit office somewhere, they are often the esteemed leaders in their profession, sporting the highest credentials.

Once you have danced with the devil of course by hiding beneficial ownership and abusing public power, its a slippery slope to numerous other crimes.

Why pay tax? Why pay royalties? Why strike honest agreements? Fraud, tax evasion, and other illicit techniques, thus are all the calling card of the kleptocrat.

In the case of Diro, he appears from the CoI account to have been a prototype that failed. Kleptocracy learnt from his mistakes.

Now we have a nation led by kleptocrats, working with crooked foreigners, to loot the nation. They hide their misdeeds through legal shams, aided by gold collar professionals, who walk around Port Moresby with an air of untouchability and arrogance.

And of course, foreign jurisdictions gladly house their illicit wealth. While the average joe on the street who falls ill, lines up in an overcrowded ward to receive counterfeit pharmaceuticals, the kleptocrats go to Australia, Singapore or the Philippines, to receive first class service, driving around in high priced cars, often flaunting their wealth on Facebook.

Their children know nothing of the struggles faced by ordinary Papua New Guineans. Snug in the beds provided by top Australian boarding schools, the world is their oyster.

And if anyone dares to level an allegation against these kleptocrats, they are the first to grab the bible, and boast saintly credentials and their years of sacrifice to the nation.

If they ever face Court – most do not – it ends, at the very best with a sentence they will never serve. Because the second a sentence is passed, these kleptocrats are granted sick leave, and walk around Port Moresby with a beer in their hand, in the firm belief nothing will ever change, their impunity is assured.

These are the poisoned fruits the nation reaps from seeds planted many years ago.

We were once a country of hope. We were a country born of diversity. We were a country born from many different histories. We were a country united by a belief in social justice. We were a country committed to fighting the ills that had seen so many post-colonial nations falter.

Where did it go wrong? Can it be salvaged? Who will lead? How will it be done?

These are the questions to which future generations need an answer.