PNGi INVESTIGATES

UBS Bank, a global serial offender, overcharged PNG A$175 million report claims

UBS Bank has gained notoriety in Papua New Guinea for its prominent role in the government’s disastrous 2014 purchase of Oil Search shares which has ended up costing ordinary taxpayers more than K1 billion in total.

In the most recent evidence submitted to the ongoing Commission of Inquiry it has been alleged that UBS extracted as much as A$175 million in excessive profits from the Oil Search deal, although PNG is not the only country that has fallen victim to the Swiss based banking giant.

In today’s PNGi investigation we examine the latest evidence from financial experts on PNG’s purchase of Oil Search shares, the loans provided by the UBS Bank and the excessive fees it extracted. We also look at UBS’s international record of law breaking to see how UBS treatment of PNG is part of a bigger global pattern of egregious behaviour.

First though, we provide a brief recap of the Oil Search share purchase and its aftermath.

A recap in brief

In 2014 the government of Peter O’Neill made the financially disastrous decision to buy a 10% stake in the oil and gas company Oil Search Limited.

Rather than delivering any positive returns, the investment was financially ruinous. Over three years the State incurred massive losses as the value of the Oil Search shares fell and the refinancing costs ballooned.

When the government was forced to sell the shares in 2017, the total losses to the taxpayer amounted to around K1 billion.

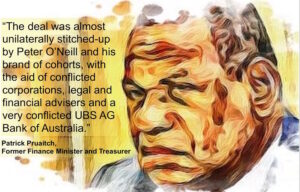

According to an Ombudsman Commission report, which was delayed for three-years by legal action by Peter O’Neill, the initial deal was arbitrarily cooked up by Peter O’Neill and Oil Search Managing Director Peter Botten in a cosy meeting at the Grand Papua Hotel in February 2014.

To fund the purchase, the national government borrowed A$1.24 billion from the Australian arm of Swiss banking group UBS.

According to the Ombudsman Commission, the loan deal was unlawful and as many as fifteen different laws were broken by Peter O’Neill and his cohorts. Peter O’Neill staunchly defends his government’s actions and maintains that he did nothing wrong.

According to the Ombudsman Commission, the loan deal was unlawful and as many as fifteen different laws were broken by Peter O’Neill and his cohorts. Peter O’Neill staunchly defends his government’s actions and maintains that he did nothing wrong.

There were though two major beneficiaries of the scheme. UBS itself, which made as much as A$175 million in windfall profits as we reveal below, and Oil Search Limited.

As a result of the timely injection of A$1.3 billion from PNG taxpayers, Oil Search was able to buy a lucrative $900 million stake in the Elk-Antelope gas field in PNG and avert any threat of a rumoured takeover.

Following the delayed release of the Ombudsman Commission report, in August 2019 the government of James Marape ordered a full Commission of Inquiry to look into the decision to purchase the Oil Search shares and UBS loan deal.

The COI has been tasked with establishing the facts surrounding the whole transaction, including all persons and entities involved in the deal and whether or not the deal followed proper and legal process and procedures.

The COI was due to report by 30 September 2021 but has requested the government grant it an extension. No formal decision on that request has yet been announced.

The Brattle Findings

The Brattle Group is an international consultancy firm that ‘answers complex economic, regulatory, and financial questions for corporations, law firms, and governments around the world’.

Brattle have been engaged by the UBS Commission of Inquiry to provide expert evidence on the terms of the financial transactions connected with the government’s purchase of shares in Oil Search Limited.

The first Brattle Report, dated July 2021, looked at the background to the Oil Search share purchase in March 2014, the terms of the UBS loan and the price paid for the shares. A second report provided further background information on the analysis presented in the main report.

Brattle Group was then asked to prepare a further report looking at financial transactions that occurred after the initial share purchase in March 2014 and to analyse further information that had come to light since their initial reports.

The Third Brattle Report submitted to the Commission of Inquiry was presented in August 2021. It is available via the UBS COI website.

The Third Report reveals that there were, in total, four loan agreements between the State and UBS in relation to the March 2014 purchase of shares in Oil Search:

- The initial ‘Bridge Loan’ and ‘Collar Loan’ taken out in March 2014.

- A second ‘Collar Loan’ taken out in December 2014 and used to repay part of the March 2014 Bridge Loan,

- A third ‘Collar Loan’ taken in February 2016 and used to repay the two earlier collar loans.

The third collar loan was repaid in September 2017 when the Oil Search shares were ultimately sold.

According to the Brattle report, at each stage of the saga, UBS was overcharging the PNG government for the loans that it provided. The total amount that was overpaid by the PNG taxpayer to UBS is calculated to have been A$ 175 million (or K450 million). This represents over 50% of all the monies paid by the State to UBS in relation to the share transactions, which was $336 million.

The Brattle report breakdown the overcharging into several separate tranches.

1. The December 2014 collar loan

When UBS provided the December 2014 collar loan, the PNG government was overcharged by AUD $7.1 million.

This overcharging was comprised of two elements. Firstly, the interest rate that was applied was higher than was justified leading to an excess transfer of $3.7 million.

Secondly, UBS billed the government for an additional premium of $2.5 million. Not only was this premium totally unjustified, according to Brattle, it was UBS that should have been paying the PNG government $900,000 for their business.

In total, therefore, says Brattle, the December 2014 Collar Loan cost the PNG taxpayer AUD 7.1 million more than it should. That $7.1 million windfall ended up in the hands of UBS.

2. The February 2016 transactions

In February 2016 the government negotiated with UBS to replace its existing collar loans with a new one.

This according to Brattle, was a strange decision for the government to have made. If the existing March 2014 and December 2016 loans had been allowed to mature between March and July 2016, according to their terms, the government could have received as much as $A390 million, depending on the prevailing market price for the Oil Search shares.

But, rather than allowing the loans to mature, on 22 February 2016 the government replaced them with another loan. On that date, Brattle estimates, based on the market price for the Oil Search shares the value of the two loans was approximately $127.9 million. UBS did not though pay the PNG government a single cent for giving up its shares

The interest rate charged by UBS under the new loan was 3%. This was significantly lower than the rate under the two previous loans (4.95%) but was still higher than a fair market rate (1.76%) according to Brattle. This, says Brattle was ‘not consistent with fair pricing or what we would expect to see from a competitive process to determine financing terms’.

In total, Brattle estimates the fair price for entering the February 2016 loan would have been A$191 million. Against this should have been offset by the monies the government was entitled to be paid for unwinding the two earlier loans which was $127.91, giving a fair aggregate price overall of A$63 million.

Rather than the fair aggregate price of $63 million, the government paid UBS $101.8 million. Thus an additional $38.8 million was transferred from the government to UBS, according to Bratle.

3. The September 2017 transaction

As with the earlier collar loans, if the February 2016 loan had been allowed to mature according to its term, rather than making any additional payments to UBS, the government could have received up to $166.9 million between February 2018 and August 2019. The actual amount would have depended on the prevailing market price for the Oil Search shares.

When the government chose to repay the loan on 21 September 2017, Brattle estimates its market value was A$154.3 million. This is money that UBS should have been willing to pay to the PNG government. Instead, the government accepted $17.6 million less. Brattle’s conclusion is that the government was not being properly advised.

4. Dividends

During the period of the second collar loan, according to Brattle, UBS retained A$17.8 in dividends paid by Oil Search on the shares that were owned by the PNG government. In total, says Brattle, the government lost out on payments of approximately $20.6 million and an additional $7.8 million in additional value that would have accrued to the value of the loan.

Thus an additional AUD 28.3 million of value was transferred to UBS as a result of the treatment of dividends in the February 2016 Collar Loan.

5. Summary

In total there were seven related transactions between the State and UBS related to the purchase of Oil Search shares.

According to Brattle’s analysis, the amount paid by the State to UBS under these transactions was A$174.8 million more than it would have been if the transactions had been fairly priced.

While the State ended up paying UBS a total of $80.9 million, if the transactions had been fairly priced, the State should have received $94 from UBS, says Brattle.

Brattle concludes that the government was not ‘adequately informed and advised’ and failed to implement a process that delivered a competitive financing solution.

When the State’s losses on the fall in value of the Oil Search shares is included, the total cost to the State of its transactions with UBS was A$336.3 million.

The $336 million is though not the total cost of the Oil Search share ownership fiasco. It does not include the sums paid by the government to other advisors such as Norton Rose Fulbright, Pacific Legal Group and even Ashurst, the lawyers advising UBS, and KPMG.

Once the findings of the UBS Commission of Inquiry are finally published we will hopefully have a better understanding of why the government was so poorly informed and advised and who should ultimately be held accountable.

UBS international charge sheet

A question might arise in light of the evidence of overcharging by UBS is was UBS the type of bank the government ought to have been dealing with? What was its track record like? Well lets take a look.

UBS is a Swiss based multinational investment bank and financial services company. It has offices in all the major financial centres and is the largest private bank in the world. It has also been embroiled in some major high-profile scandals. These include helping wealthy French and Americans evade taxes, manipulating international interest rates and failing to prevent one of its traders from running up more than $2 billion in losses. Globally the firm has paid millions of dollars in fines and law-suit settlements and, in 2015, it had to plead guilty to a criminal charge in the United States.

According to the Violation Tracker website, UBS has paid a total of 98 different fines and penalties since 2000, totalling almost US$17 billion.

Most of the its offences were financial in nature, 77 out of the total of 98.

![]()

Table reproduced from the Good Jobs First Violation Tracker website, accessed on October 26, 2021.

The highest penalties were paid for investor protection violations. The second highest amount of penalties were paid for interest rate benchmark manipulations.

![]()

Table reproduced from the Good Jobs First Violation Tracker website, accessed on October 26, 2021.

In January 2020 it was announced that UBS was being probed by prosecutors in Milan over allegations it helped an Italian wealth firm defraud 117 clients of 6 million Euro. Prosecutors accuse UBS of hiding the fraud by obstructing authorities and failing to report the transactions.

In February 2019, a French court found UBS guilty of illegally soliciting clients and laundering the proceeds of tax evasion. UBS was ordered to pay $5.1 billion in penalties. The court found UBS had illegally helped French clients hide billions euros from French tax authorities between 2004 and 2012.

The French prosecutors had previously told the court UBS was “systematic” in its support of tax-evading customers and that the laundering of proceeds from the tax fraud was done on an “industrial” scale.

UBS is currently appealing against the French fine and a court decision is expected in December.

Following a similar case in the United States in 2009, UBS paid a settlement of $780m and in 2014 it agreed to a €300m fine in Germany.

In 2018, UBS paid $230 million in penalties in the United States for defrauding investors in the sale of residential mortgage-backed securities which contributed to the 2008 global financial crisis.

According to US prosectors the crisis resulted ‘in lasting economic harm to the nation and unnecessary suffering for Americans’. Investors who bought from UBS ‘suffered catastrophic losses’ as a result of being misled and denied crucial information.

In December of the same year, UBS also paid $68 million to another U.S. state attorney general to resolve allegations of manipulating the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR). LIBOR is the rate at which banks lend money to one another and is a key financial tool that determines interest rates for many financial products, including government and corporate bonds. During the financial crisis, large international banks manipulated LIBOR to enhance their financial health, avoid negative publicity, and minimize harm to their reputations. They did so at the expense of investors.

Also in 2018, UBS was ordered to pay $19.8 million in a Puerto Rico bond fraud case.

“The business model was to put their interests first, ahead of their own clients, push their clients to the back, we’re going to take care of us, we’re going to take care of our bottom line, take care of our bonus pool, and our clients come second.’”

The court found UBS encouraged its wealthy clients to invest heavily in high-risk bonds without disclosing the risks or considering their client’s actual goals. Many UBS clients ended up being forced to liquidate their live savings and were left with nothing.

In 2017 the National Credit Union Administration, another arm of the United States government, announced that it had collected $445 million from UBS to resolve claims by two credit unions that had been sold toxic securities.

The Corporate Research Project has documented a more extensive list of UBS fines and other settlements

In 2016, UBS assets in Singapore were seized as part of investigations into the Malaysian state investment company, 1MDB fraud. It is alleged more than $3.5 billion was misappropriated and about $1 billion was laundered through the US by the Malaysian company. UBS was one of four banks to have £133 million in assets seized according to media reports.

In September 2016 the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) announced that UBS would pay more than $15 million to settle allegations that it failed to adequately educate and train its sales force about critical aspects of certain complex financial products it sold to retail investors.

In May 2015, UBS was fined $342 million by the U.S. Federal Reserve for currency manipulation and had to pay $14.4 million to settle SEC allegations that it created an uneven playing field for investors inside its “dark pool” alternative trading system.

Also in 2015, the U.S. Justice Department announced UBS was in breach of its 2012 LIBOR settlement and would plead guilty to a criminal charge, pay a fine of $203 million and go on probation for three years.

In November 2014 UBS was fined $290 million by the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, $371 million by Britain’s Financial Conduct Authority and $138 million by Swiss authorities as part of a settlement of charges that it and other major banks manipulated the foreign exchange market.

In 2013 UBS was fined £9.45 million by Britain’s Financial Services Authority for a variety of failures in connection with the sale of risky securities linked to AIG.

Later that year, the SEC announced that UBS would pay $50 million to settle charges that it misled investors during the sale of collateralized debt obligations.

In 2012, UBS was fined £30 million in the United Kingdom for failings which allowed a rogue trader to commit the biggest fraud in UK history. The trader was jailed for seven years after secretly racking up losses of £1.4 billion. UK regulators blamed ‘seriously defective’ systems and controls at UBS for the scale of the fraud which had ‘damaged confidence in the integrity of the markets and the financial system’.

UBS had previously be fined £8 million for similar offences in the UK in 2009.

In 2012, UBS was caught up in another scandal over manipulation of the LIBOR interest rate. In December 2012 the Japanese securities subsidiary of UBS pleaded guilty to a charge of felony wire fraud in U.S. federal court and consented to pay about $1.5 billion in penalties and disgorgement to settle that charge and additional cases brought by other regulators in the United States, Britain and Switzerland. By negotiating to have the Japanese unit make the plea, UBS ensured that its U.S. operations would be not affected. During a subsequent hearing on the case in the British Parliament, several former UBS executives were accused of “gross negligence and incompetence.”

Before the year was over, UBS was also fined $12 million by the U.S. financial industry regulator (FINRA) for violating short sale regulations and had to pay $8 million to settle short-sale charges brought by the SEC.

In 2011 FINRA fined UBS $2.5 million and ordered it to pay $8.25 million in restitution to customers who were said to have been misled when purchasing securities known as 100% Principal-Protection Notes. That same year, UBS agreed to pay $160 million to settle federal and state charges relating to bid-rigging in the municipal securities market. A month later, UBS was sued by the Federal Housing Finance Agency in an action seeking to recover more than $900 million in losses suffered by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from mortgage-backed securities purchased through UBS. In July 2013 the agency announced that UBS would pay $885 million to settle the case.

In 2010 UBS agreed to pay a fine of $6.6 million and buy back $200 million of auction rate securities to settle charges of deceiving investors in Texas.

in 2009, UBS agreed to pay $780 million in penalties and enter into a deferred prosecution agreement to settle criminal charges of having defrauded U.S. tax authorities.

In 2008 UBS agreed to pay about $282 million to settle legal claims relating to its role in financing Parmalat, the Italian dairy company that collapsed in 2003 amid charges of fraud and money laundering. That same year, UBS was hit with lawsuits filed by several U.S. state governments relating to its sale of auction-rate securities. UBS settled the actions by agreeing to pay a total of $150 million in penalties to the states and buy back more than $18 billion of the securities.

In 2007 FINRA fined UBS $370,000 for making hundreds of late disclosures about its brokers and another $250,000 the following year for supervisory failures related to improper mutual fund sales.

In 2006, another government lawsuit in the United States accused UBS of defrauding thousands of its customers with false and misleading promises and excessive fees. It was alleged customers overpaid tens of millions of dollars.

The lawsuit alleged violations of ant-fraud laws, common law fraud and breaches of fiduciary duty.

In 2006 UBS was again fined in the United States, this time $49.5 million for market-timing violations.

In 2004, the U.S. Federal Reserve fined UBS $100 million for violating U.S. trade sanctions by engaging in currency transactions with parties in countries such as Iran and Libya.

For earlier fines and penalties imposed on UBS and its predecessors see the Corporate Research Project website

As the old saying goes, you lie down with dogs, you wake up with fleas. In the case of PNG though, its the taxpayers who have to pay the price.