THE TOKAUT BLOG

Whistleblower law completely unfit for purpose

Whistleblowers can play an essential role in exposing corruption, fraud and mismanagement. But they often do so at great personal risk. Therefore, comprehensive legal protections are a vital part of any anti-corruption framework.

The government has acknowledged the dangers faced by whistleblowers in Papua New Guinea and enacted the nation’s first-ever whistleblower protection law. Unfortunately, the Act completely fails in its stated purpose of protecting whistleblowers from harm, and may even make their situation more perilous. It also fails to impose an obligation on employers, including government departments, to encourage and support whistleblowers, or investigate their complaints.

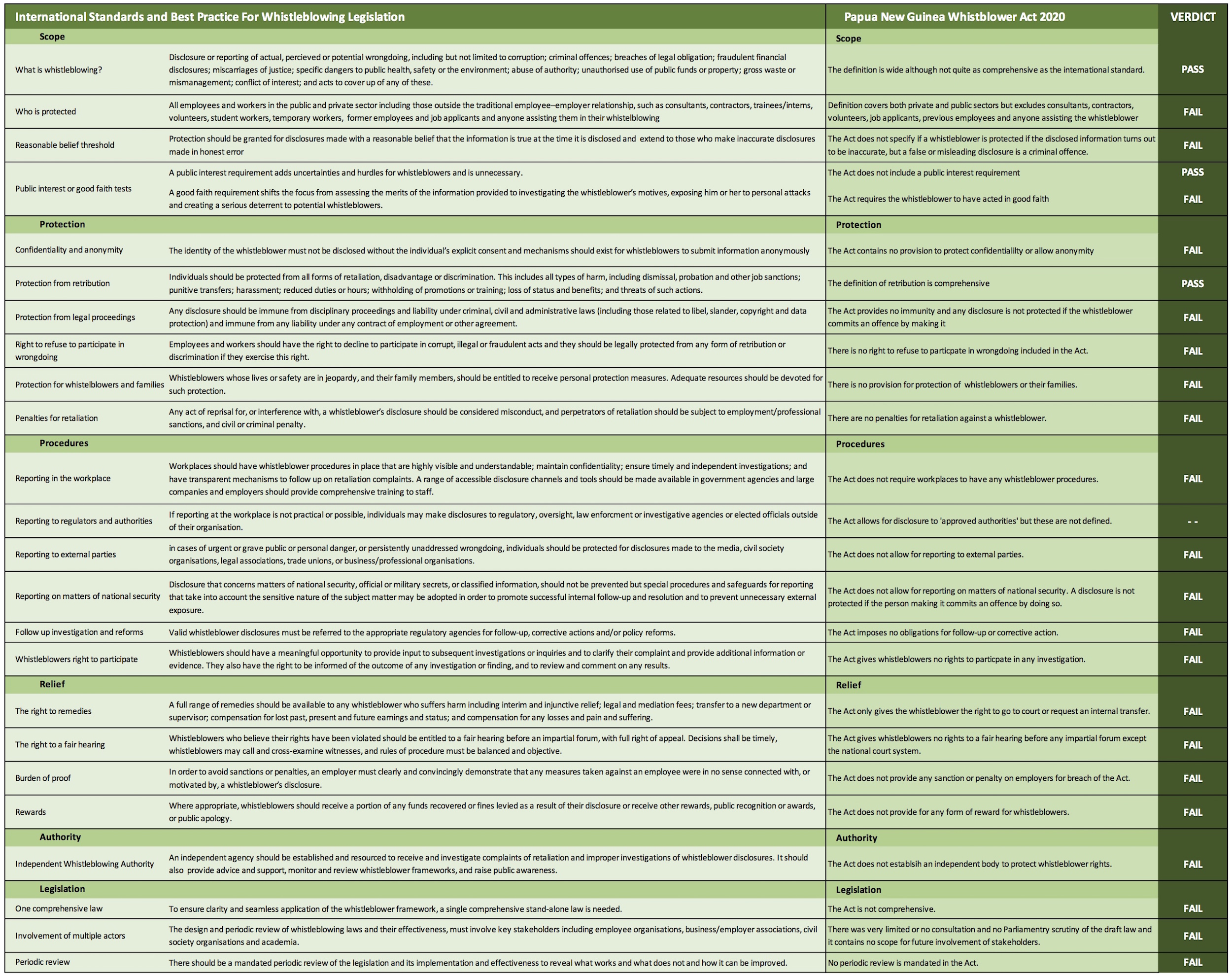

The Whistleblower Act, certified into law on May 6, is supposed to be part of the government’s commitment to tackling chronic corruption, yet analysis by PNGi shows the Act meets just three out of twenty-four International Best Practice Guidelines.

Transparency International has published a best practice guide for whistleblowing legislation that the PNG government has completely failed to follow

While the law makes it unlawful for an employer to take any detrimental action against a whistleblower, such as sacking, demotion or other forms of harassment, the protection is seriously limited in its applicability, and fails to impose any penalty on employers for breach.

The Act’s protection only covers paid employees, not volunteers, interns or students. Critically, the Act expressly excludes consultants and other outside contractors from any protection.

The law also only protects an employee who makes a report of impropriety to his immediate supervisor or ’employer’ – the exact people the whistleblower is most likely to be complaining about. The Act imposes no obligation on the employer to conduct an investigation, or take any other action.

If the employee’s complaint is not acted on and they then report the matter to any other person, whether inside or outside the organisation, they are not protected unless the complaint is made to an ‘approved authority’. What constitutes an approved authority is not defined beyond giving the responsible Minister the power to proscribe at a later date.

The law also imposes no penalty on an employer for breaching the Act and the only remedy for a sacked or demoted whistleblower is to make an application to the courts – which will be beyond the means of most employees, while any court litigation could drag on for years.

Also, there is no obligation on the employer to protect the identity of the whistleblower or provide a system for whistleblowers to report matters anonymously. The law fails to mandate that employers and government departments must have a system for dealing with whistleblower complaints.

As is typical of most new laws in PNG, the government completely failed to consult publicly on the draft bill. It was passed without any proper Parliamentary scrutiny. The new law was even kept secret for four months after being passed by Parliament.

The government has touted the Whistleblower Act as forming a key part of its anti-corruption strategy. By failing to provide any measure of proper protection, the government seems to be signalling instead that it does not support a culture of whistleblowing.

It has missed a major opportunity to improve openness and accountability and expose and stop the theft and misuse of public funds.

What the law says

The Whistleblower Act 2020 is just four-pages long and contains 15 Sections. It states that its purpose is to protect whistleblowers from occupational detriment.

The objectives (Section 3) are to provide procedures for employees to report improprieties, protect those employees from occupational detriment and provide remedies to those who do suffer.

An employee is defined as any person who works for someone else and is paid for their work. Independent contractors are expressly excluded.

Impropriety includes criminal offences, failure to comply with legal obligations, miscarriage of justice, endangering health and safety, environmental damage and unfair discrimination.

The only protected disclosures are those made to a lawyer in the process of seeking legal advice; to an employer or an immediate supervisor; to a government Minister if the employee is not a public servant but is employed by a statutory body; or to an ‘approved authority’ if the disclosure relates to the functions of the authority.

There is no protection if the person commits an offence by making the disclosure.

The Act states an employer must not subject a whistleblower who makes a protected disclosure to any occupational detriment including disciplinary action, demotion, harassment, transfer, altering their employment terms, denying promotion or giving an adverse reference.

If a whistleblower does suffer occupational detriment they can apply for a transfer which must be accepted if ‘reasonably practicable’ or may apply to the court for ‘appropriate relief’.

A false or misleading disclosure by an employee is an offence punishable with a fine of up to K10,000 or six months prison with hard labour.

International Best Practice

In 2013, a set of International Principles for Whistleblower Legislation were published. They are reflected in similar guidance from the United Nations, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Council of Europe.

In 2018, Transparency International published ‘A Best Practice Guide for Whistleblowing Legislation’ to assist policy makers implement the Principles.

Together, the Principles and Best Practice Guide identify 24 standards which whistleblower legislation needs to meet in order to provide comprehensive and effective protection.

A careful examination of the Whistleblower Act against those standards, reveals the new law only meets three out of twenty-four.

The only positive thing that can be said about the PNG legislation is that it provides good definitions of what is whistleblowing and what can constitute retribution, and it does not impose a public interest test.

On every other measure the legislation fails.

Most critically, the law:

- does not cover whistleblowers who are consultants, contractors, volunteers, job applicants, previous employees or anyone assisting the whistleblower;

- does not protect whistleblower confidentiality or allow anonymous reporting;

- does not protect the whistleblower from other legal liabilities;

- does not protect employees who refuse to participate in wrongdoing and therefore suffer harm;

- does not protect whistleblowers or their families from retribution outside the workplace;

- does not impose penalties on employers for taking retaliation;

- does not require workplaces to have official whistleblower procedures;

- does not impose any duty to on employers to follow up on complaints or to do so fairly and impartially; and

- does not establish an independent body to protect whistleblower rights.

Why protect whistleblowers?

Whistleblowers play an essential role in exposing corruption, fraud, mismanagement and other wrongdoing that threatens public health and safety, financial integrity, human rights, the environment, and the rule of law. By disclosing information about such misdeeds, whistleblowers around the world have helped save countless lives and billions of dollars in public funds, while preventing emerging scandals and disasters from worsening.

Whistleblowers often take on high personal risk. They may be fired, sued, blacklisted, arrested, threatened or, in extreme cases, assaulted or killed. Protecting whistleblowers from unfair treatment, including retaliation, discrimination or disadvantage, can embolden people to report wrongdoing and thus increase the likelihood that wrongdoing is uncovered and penalised. Whistleblower protection is thus a key means of enhancing openness and accountability in government and corporate workplaces.

The right of citizens to report wrongdoing is part of the right of freedom of expression, and is linked to the principles of transparency and integrity. All people have the inherent right to protect the well- being of other citizens and the common good of society, and in some cases they have a professional or legal duty to report wrongdoing. The absence of effective protection can therefore pose a dilemma for whistleblowers: they are often expected to report wrongdoing, but doing so can damage their career or expose them to retaliation.

All global and regional treaties aimed at combating corruption have recognised the importance of whistleblower protection to address corruption, and have introduced requirements to protect whistleblowers. This includes the United Nations Convention against Corruption, the Council of Europe Civil and Criminal Law Conventions on Corruption, the Inter-American Convention against Corruption, the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption and the Arab Convention to Fight Corruption.

This section is reproduced from ‘A Best Practice Guide for Whistleblowing Legislation’, 2018.